|

|

05/26/60 - 04/29/95

Grieving and Healing After a Murder

Clara Maberry, NMSOH Member - Article by Sally Lamas 04/05/00

There comes a knock on the door or a

telephone call. Words are spoken that can’t be erased. A range of emotions surges

like waves---shock, rage, grief, numbness. How does one cope with the loss of someone who

has just died? How does one cope with a murder?

Clara Maberry, a member of the New Mexico Survivors of Homicide, Inc. (NMSOH), has some

answers of her own to these questions. Five years ago, her 34-year-old son, Mark Maberry,

was murdered in a hotel room off of Central Ave. and San Mateo Blvd. in Albuquerque. Clara

and her husband, two surviving children, grandchildren, and Mark’s friends have felt

the effects of his death. She said they would continue to feel his absence for years to

come.

When Clara considered how her son’s death affects her outlook on her family, she

said: "I worry that my grandchildren might get hurt. They say to me, ‘Grandma,

don’t worry so much!’ But I can’t help it. The shock of a murder is so bad

and so extreme. I feel unsafe."

The Albuquerque Police Department reported that 75 homicides occurred last year, 1999, in

Bernalillo County. Fifty of those homicides happened within Albuquerque city limits and 25

of them in unincorporated areas.

The published facts don’t necessarily help us understand how we, or others we know,

are affected by these murders. A brochure published by the NMSOH states the following:

"Homicide survivors are subjected to stresses not faced by others whose loved ones

have not been murdered, e.g., media attention, protracted legal proceedings, contacts with

law enforcement, and isolation at a time when they are most in need of love and support.

Few people in our society know how to respond appropriately to someone who is devastated

by the murder of a loved one. Consequently, survivors are often avoided." The NMSOH

was officially recognized as an incorporated, non-profit group in 1997 and strives to

provide that critical support, education, and advocacy for all homicide survivors in New

Mexico.

Clara said she has learned a lot during her involvement with the NMSOH, but more

importantly, she has found some sort of peace for herself. Now, five years after her

son’s death, Clara said: "I don’t break down as much, but there’s

still a void. Sometimes when I miss Mark, I also feel something else missing—the

worry. I didn't realize I had so much worry about him until he was gone. Once I knew I

didn’t have to worry anymore, I could start healing.

"Today, I just take life as it comes and I hope and pray. I believe everything

happens for a reason," Clara said. She reminisced that right before he died, Mark

took a train trip to California to see his grandma and extended family. This was something

she said he had always wanted to do. When Clara met him at the station on his return, she

said she saw a halo of light over his head. "At that moment, something told me I

wouldn’t have him long. Maybe it was a sign."

Clara shared that many family survivors of homicide experience events that seem almost

mystical. "Sometimes I feel Mark nearby and I can even smell him," she said.

"I also have dreams about him. I was sleeping in the other morning, and right before

I woke up, I saw him in my dream. It felt so good to see him, even in a dream."

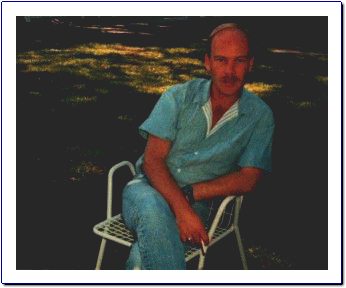

From her seat on the sofa in a comfortable back room at the office of the NMSOH, Clara

shared a few photographs of Mark. He had receding, sandy blond hair and a neatly trimmed

mustache. His eyes sparkled with life and he wore a smile that seemed natural and content.

Clara recalled his history and his struggles.

Clara and Larry Maberry moved from California to Albuquerque in 1972 with their three

children, Rick, 13, Mark, 12, and Patty, 9. Clara worried about her middle son because he

had developed a form of juvenile diabetes. Despite his early struggles, Mark graduated in

1978 from Rio Grande High School, attended classes at TVI in the field of respiratory

therapy, lived and worked in California in **year?**and then returned to New Mexico

**year?**. For 8-10 years, he held a variety of positions as a waiter in

Albuquerque’s Old Town restaurants where people knew him well and considered him a

friend.

In his adult years, Mark developed macula cysts on his eyes from the diabetes. Despite 5

previous laser surgeries from the late 80’s to the early 90’s, he became legally

blind in one eye and had trouble seeing in the other. "I worried about him a

lot," Clara said. "He took insulin shots four times a day and was frequently in

and out of the hospital with insulin reactions. In my heart, I feared I would lose him

some day to the disease."

Mark moved in with his parents in 1991 when he could no longer drive. Instead, he rode the

bus to his job as a headwaiter in Albuquerque’s Old Town area. "He told me he

had to stay independent and keep working," Clara said. "He didn’t want to

go on Social Security and receive disability income. He enjoyed his work." Clara said

she loved having him around the house and she felt better knowing she could help him if he

needed it.

"We’ve always been a close family," Clara said. "I loved having Mark

around the house again." Just before Mark died, his younger sister, Patty, had just

given birth to a baby boy. "This baby gave Mark so much pleasure," Clara said.

"On the day that Mark died, he was late to work because he stopped to hold and rock

the baby. When I offered him a ride to work instead of taking the bus, he said he’d

just be late. He didn’t want me to cancel any of my appointments."

That day, on Friday, April 29, 1995, Mark went to work as the headwaiter at Conrad’s

Downtown restaurant located in the historic La Posada de Albuquerque hotel. He usually

worked until 11:30 p.m. when one of his parents would come pick him up. He called later

that night to say he would be staying downtown for a friend’s birthday party and that

he’d get a hotel room for the night.

Clara said she didn’t think anything of it when Mark didn’t come home Saturday

morning from the previous night’s party. Around noon, she and her daughter went

shopping. "When we came back," she said, "my husband was working in the

yard and he looked up at us with such a mad face that I wondered what we’d done to

make him so angry. That’s when he told us that Mark had been stabbed to death in a

hotel room the night before. "It was like a shock through me. My daughter started

crying and screaming. All I could think of was that I had to protect my family."

Clara learned that a homeless man had been talking to Mark all evening at the bar where

Mark and his friends were celebrating a birthday. At the end of the night, the stranger

asked if he could stay with Mark in his hotel lodgings downtown and Mark allowed him to.

When the hotel maid came to clean their room the next morning, she found Mark lying in

blood, face down on the bed of the hotel room. Investigating police found that Mark had

been stabbed more than 35 times all over his body, his spinal chord and throat cut, and

his head scalped. By 1 p.m. that Saturday the police found and notified Mark’s

family.

An hour after the initial shock of the news, Clara had to call friends and family to tell

them the news. "So much was going on. I was doing all of this, yet I was in a fog. I

was frozen inside, but my biggest concern was taking care of the rest of my family."

The next morning, Clara said she got up early, before anyone else and went into the

bathroom and cried her heart out. "When you lose somebody through murder, it is just

the worst," Clara confided. "There's a big red and black spot, like an

explosion, inside yourself. This is not a natural death. It is not someone dying after a

long illness or a long life. If my son had died from the diabetes, I could have accepted

it. I can't accept this, but I have to in order to go on."

When a detective came that morning to gather information on Mark, the house was already

filled with family gathering for the memorial. The detective asked to meet privately with

Clara. "It was a very hard thing to do by myself without my husband and my

family," Clara said. "I just wanted to be helpful but I felt so numb. I'm

surprised I remember much from that day."

Like many survivors of homicide, Clara not only had to deal with her own loss, but she had

to participate in a legal case and to talk to strangers about her son, his activities and

his death. "It really scared me that my son's murder might be sensationalized,"

Clara said, "but we didn't get a lot of media attention because three other murders

happened in Albuquerque that same weekend."

Reflecting on her son’s memorial, Clara said, "I remember thinking how much I

didn’t want this to be happening." She said it was extremely difficult not only

because it was the first death in her immediate family, but also because no one knew yet

who had murdered her son or why.

Family and friends got up at the service to talk about Mark, others sat with Clara and

told her stories about him. Restaurant friends from Old Town brought food for the family.

"It was a day to celebrate his life," she said. She recalled a humorous moment

during the memorial when the minister quoted her daughter, Patty, and accidentally called

her Patsy Cline. "That made us laugh because one of Mark's favorite songs was,

'Walking After Midnight' by Patsy Cline and we had to ask ourselves, ‘Did Mark make

the minister do that?’"

Eventually family had to leave and go back home. "It got rough then," Clara

said, "because I had to keep going and live each day at a time." She observed

that the grieving process takes different forms for different people. "My husband

still has a hard time dealing with Mark’s death and doesn't really want to talk about

it because he says it hurts too much. He doesn't get involved with any support programs,

but he is supportive of my desire to do so," Clara said. She said that her daughter,

Patty, talks freely and tells stories about Mark to her 5-year-old son, but older son,

Rick, avoids referring to Mark for fear of upsetting the family. "Sometimes, though,

when we all get together we will start remembering the fun times we had as a family with

Mark," Clara said. "I really enjoy that."

Six months after Mark’s death Clara said she started looking for outside support and

found a pamphlet describing the Grief Services Program offered through the New Mexico

Office of the Medical Investigator (OMI).

In 1995, grief counselors Ed Candelaria and Liz Adkins from the OMI held two 8-week

support groups to serve about 20 families in the Albuquerque Metropolitan Area whose

children had been murdered. After the first 8 weeks ended, members said they felt so close

that they wanted to keep meeting regularly each month. Candelaria and Adkins continued to

facilitate these gatherings at the OMI over the next four years. The meetings allowed

members to grieve and process their experiences together. Adkins said, "Sometimes

family and friends of a murder victim feel like they’re really going crazy, but when

they come together to talk, they can see their feelings are normal under the

circumstances."

Clara commented on the support group: "Sometimes I'd leave in worse shape than when I

got there. I'd get home and wonder why I went, but then, by the next month I'd be ready to

go again. Bringing up my son's death hurt, but it was also helpful. It was like

nourishment to talk about it and I kept coming back for more."

Clara said she felt relief when Mark’s alleged murderer was found two weeks after the

killing. Her family attended three court dates over a year’s time for the indictment,

plea-bargaining and sentencing. "It was hard to wait for it to be over," she

said, but noted that having the support group gave her strength. "The other survivors

read the newspapers and kept up with the case. We talked about it at our meetings and I

could share what was happening with me."

Clara said her reaction to the accused man surprised her. "I had already seen the

composite drawing of the alleged murderer and later, his face on TV, but seeing him in the

courtroom filled me with an anger I didn't know I had in me," Clara said.

"During one court date, he looked over and smirked at us. I don't know if it was

really a nervous laugh, but it was a smirk to me. What really upset me," Clara

continued, "was that this man left Mark to suffer and die alone."

The accused man plea-bargained from first-degree murder down to second-degree murder and

was sentenced to 15 years in prison. Clara said he would probably serve 7 ½ years and

then be released on parole, but she said her family’s case had achieved a better

outcome than many survivors’ had. "The judge did what he could do as far as

giving justice. It made me feel better that he let me, my husband, my son, and my daughter

speak at the sentencing. The murderer could say whatever he wanted, but someone got to

speak for my son."

The Maberrys waited until a year after the sentencing and two years after Mark’s

death to scatter his ashes. "We didn't want to give him up before then," Clara

said, "but he was a free-spirited person in many ways and we knew we had to let him

go."

This May 26, 2000 would have been Mark’s 40th birthday. For the last four

years, Clara and her family have celebrated his birth and life by going camping together

at a special place in the mountains. "We can at least be with him spiritually,"

she said.

Remembering Mark’s life and his attributes helps in the healing process, Clara said.

"In the restaurant business, Mark met many different people. He was very outgoing and

friendly and he liked everybody. When he had problems, everyone knew. When they had them,

he knew." Clara said she was proud of her son’s friendships. "He was not

prejudiced whatsoever and had Indian, Black, Spanish, and Mexican friends. Besides being

legally blind in one eye, I think he was color blind too," she said with a warm

laugh.

On days when she felt particularly sad or empty, one of Mark’s friends would call her

up out of the blue and want to talk. She said that these little brushes with her

son’s old circles lighten her sorrow. She said, "I realized it’s not just

the family that grieves, but also the friends.

"I know I can’t change anything that happened," Clara said. "We have

to continue living, like we’re supposed to. Sometimes I shock myself by getting very

angry about his death, but usually when that happens, I try to get busy with a

project." That’s where Clara said her work comes in with the NMSOH.

Clara continues to volunteer her time at the NMSOH. She takes calls, does office, attends

its weekly support meetings, and helps represent the group in its public activities.

"It makes me happy to be able to help other people. I need that interaction,"

she said. "Sometimes your family wants to get over the event, but maybe you want to

keep talking about it. With other, less traumatic deaths, people tend to get on with their

lives and let go. A murder is different because you just don't know why it happened. The

murderer gives certain reasons, but you still don't really know why."

Recently, Clara participated with a group of students from Albuquerque’s Technical

Vocational Institute in a project to create a public town hall meeting which occurred on

March 2 to address issues surrounding homicide in New Mexico. She is helping to plan this

year’s NMSOH Annual Conference to be held in **city** on**date?**. Clara also serves

on a committee with students from the UNM school of Architecture who are designing a State

Memorial Wall to be constructed in an Albuquerque public park.

In 1997, the NMSOH became an incorporated, non-profit group. It opened its first office in

Albuquerque in 1999. Since its inception in 1995, NMSOH chapters formed in Farmington, Las

Cruces, and Taos-Rio Arriba counties. The organization is trying to start additional

chapters in Roswell and Gallup to support families like Clara’s in their grieving and

healing processes.

The Grief Services Program continues to address issues surrounding traumatic death

(including: prenatal and infant death, accidental death, homicide, suicide and unexpected

natural cause) and offers crisis services, support group facilitation, advocacy, education

and referrals to community resources for bereaved families and the community.

For more information about the New Mexico Survivors of Homicide, contact the Albuquerque

NMSOH office at (505) 232-4099 or try their web site at www.nmsoh.org. For more

information about the Grief Services Program call the Office of the Medical Investigator

at (505) 272-3053.Mark L.

MaberryMark L. Maberry

|

|